My Life at Nashotah

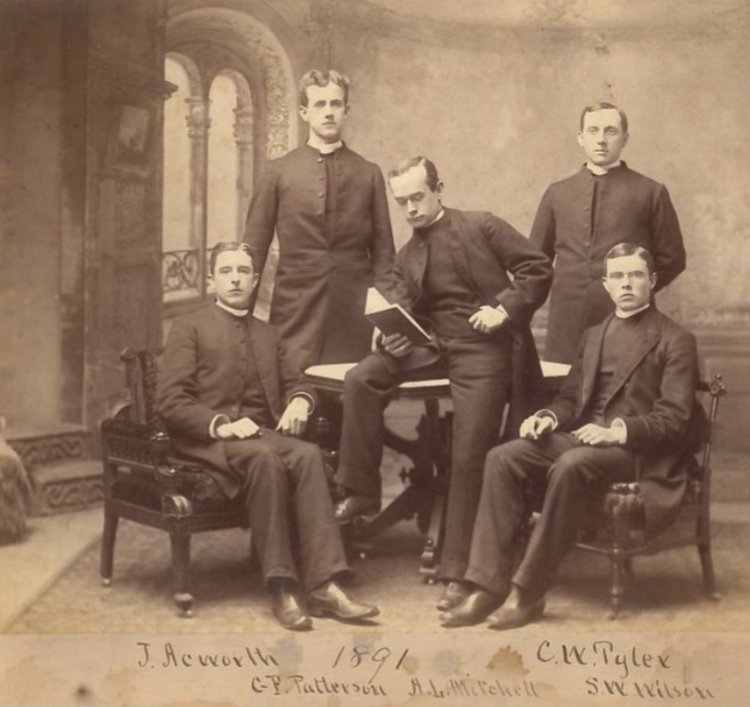

By the Rt. Rev. William Walter Webb, D.D., L.L.D., Bishop of Milwaukee, President of the Board of Trustees, President of Nashotah House 1897 to 1906, transcribed by Terry Koehler

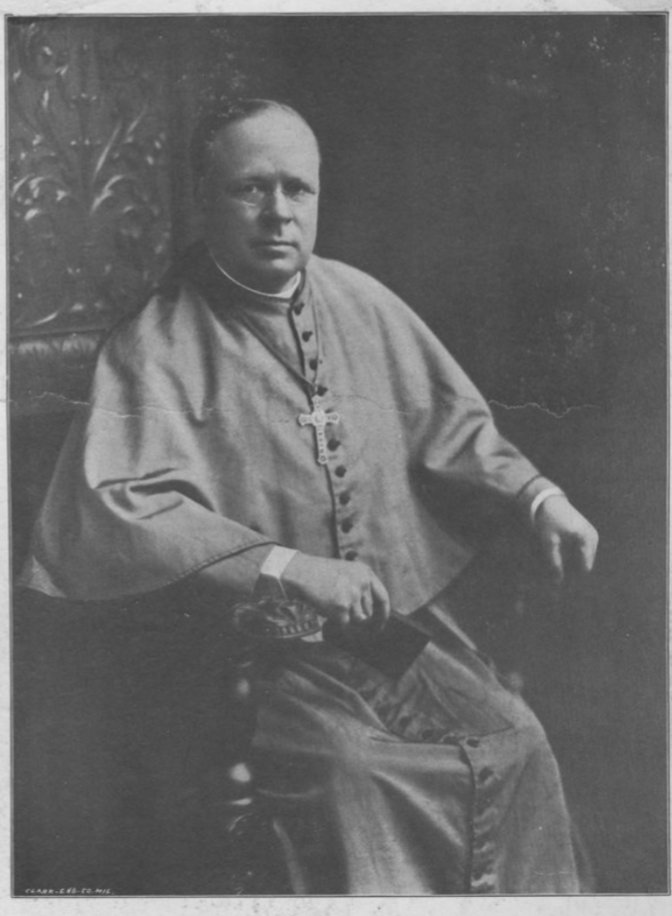

Nashotah House students c. 1900

My first visit to Nashotah House was in the Spring of 1892, very soon after the Jubilee Service. I had been giving a retreat for the Associates of Kemper Hall, and went to Nashotah, staying with Dr. and Mrs. Adams, who were then living in what was called the Dean’s House. Dr. Gardner, who was then President of the House, which was the title before “Dean,” was living at the Fort with his nephew, Walter Gardner, and Dr. Riley was living in some rooms in Bishop White Hall. The Cloister was not built, and they were just finishing Lewis Hall. I remember climbing up a ladder to get a view from the round tower.

I had been elected Professor of the Old Testament and Hebrew the year before, but as my eyesight was not good, I had to decline the chair. Dr. Adams was getting to be very old and feeble and talked with me about succeeding him. I always felt that seminary work was the most important work that a priest could do, and I still feel that. I had written a little book, “A Guide to Seminarians,” which shows that I was interested in seminary work. I was fascinated by the beauty and atmosphere of Nashotah, and after my visit I was elected Professor of Dogmatic and Moral Theology to succeed Dr. Adams, and I accepted.

I reached Nashotah on Epiphany 1893. There had been a very heavy snowstorm, and I remember riding over with Professor Clapp in a bobsled, and our being spilled out in a snow drift. At that time the faculty were all unmarried. Lewis Hall had been completed and Dr. Gardner and Dr. Riley and Fr. Clapp and myself lived in that building. Fr. Clapp and I had an oratory, I think the first St. Francis oratory on the grounds, with a window looking out over the cedar tree and Preaching Cross.

Compline was said in St. Mary’s oratory in Bishop White Hall, which was on the fourth floor. That building, by the way, when it was built, was considered the skyscraper of Wisconsin. It was four stories high. It was heated entirely with stoves, and a good many times I went to say Compline when the oratory was so filled with smoke that it was difficult to read.

The Rt. Rev. William Webb

My lecture room was in the old chapel, which Dr. Adams had used for many years. It was heated by a long cast iron stove that would hold cord wood. There was still a certain remnant of the old committee work. The men all looked after their rooms and the stoves in the various buildings and filled the oil lamps in the chapel. I used to sit in a large chair in what is now the sanctuary, and it was not unusual for the oil to drip down on me. I frequently lectured in an ulster and even a cap and gloves when the room was so cold that we all had to be wrapped up. One man, who is still living and is a priest in this diocese, was not used to looking after stoves, as he came from the south, and I used to come in and find snow on the wood and find the place filled with kerosene oil smoke and a very feeble fire. Sometimes when we got well warmed up, the squirrels would make such a rumpus on the ceiling, rolling nuts and chasing one another around, that it would interfere with the lecture.

I don’t think it has always been realized how much Dr. Gardner did for Nashotah; practically, he brought about the entire reformation of life there and introduced a rule which, with one modification and another, has continued ever since his day. He introduced the daily Mass. Nashotah has always been proud of the fact that there has been a weekly Mass there from the very beginning, since October 14, 1842. It has been claimed that weekly Mass was started in Ashtabula, Ohio, and it is also claimed by St. Peter’s Church, Philadelphia. It undoubtedly started in all these places about the same time. Dr. Gardner also introduced Compline and meditation at the early Mass, and a reading during breakfast, and daily reading during meals throughout Lent, and a sermon at Evensong. Credit has never been given to Dr. Riley for the way he carried things over when Nashotah was at a very low ebb, when, practically speaking, his catholic teaching and spiritual instructions meant everything to the small body of students.

Dr. Adams was an old-fashioned Tractarian, very strict in his observance of certain parts of the church’s discipline. He used to fast until three o’clock in the afternoon on most Fridays, and when he grew old and feeble, it was with great difficulty that he could be gotten to break that rule. He really fought out the Baptismal Controversy in this country, just as Pusey did in England. His Baptismal Regeneration was a most scholarly treatise, and he wrote a popular book with the quaint title of Mercy for Babes that had a very large circulation. His book The Elements of Christian Science was the first important book on Moral Philosophy and Moral Theology published in the American Church. Its title is a strange one in the light of the development of the Christian Science body. The book itself, which is very scholarly, was really a great contribution in a field in which little work had been done in the Anglican Church for many years. Dr. Adams was a graduate of the University of Dublin and afterward went to the General Theological Seminary. He was one of the original three who came to Nashotah, long outliving the others. He had all of an Irishman’s humor, and there were a great many quaint stories told about him. He objected to the colored vestments which Dr. Gardner had introduced but was persuaded to wear some made for him by a granddaughter to whom he was very devoted. In those days the priests vested in the little room off the sanctuary, which is now used by the servers. The chapel was not arranged choir-wise, so the congregation was seated almost up to the choir steps. There was a small railing and some benches facing each other inside the railing where the students were seated. The congregation could hear anything that was said in the sacristy, especially when Dr. Adams was talking, as he had a high shrill voice that really carried.

The Chapel of St. Mary the Virgin at Nashotah House, c. 1890

Dr. Riley and I were vesting him for the first time in his green chasuble, and he asked, “Riley, what do I look like?” We tried to prevent his talking, as we knew the congregation could hear what he was saying, but, much to our amusement and that of the congregation, he answered his own question: “Riley, I look like a heavenly peacock.”

Mrs. Adams had a very little sense of humor, and he used to often tease her by saying things she disapproved of. She used to give afternoon teas at which many of the people from the neighborhood were present and which were more generous than in these days. She prided herself on the croquettes that she made. One afternoon a good farmer, when they were offered to him, took one up, evidently thinking it was a doughnut, bit into it and said, “Gosh, it’s harsh.”

Whenever they had croquettes after that, Dr. Adams always wanted to tell that story. Mrs. Adams evidently felt that the remark was profane and always tried to head the doctor off but in vain. Mrs. Adams always thought that the doctor was going to die before she did, and when they moved into the house in which Canon St. George is now living, the Dean’s House, as it has been called, Mrs. Adams looked at the rather narrow and crowded staircase and said, “I can never get a coffin down there.” Dr. Adams said, “Never mind, my dear, I will see that it comes down.” He was a joy. I could tell story after story about him.

Fr. Clapp and Dr. Riley had their lecture rooms in the old “Turkey Roost,” which has since burned down, the only part of it that was then used. Dr. Gardner had a lecture room adjoining his rooms in Lewis Hall and I lectured in the old chapel under difficulties.

We were very much shut in during the winter, and there were no trolly or bus lines, and as there were no married members of the faculty, the students had very few places to call, except in the late spring or early autumn when there were various families living in the cottages--the Campbells and Cards and Brighams, especially. We used to have lectures often illustrated with lantern slides and things of that kind to break the monotony, especially on Saturday and Sunday nights.

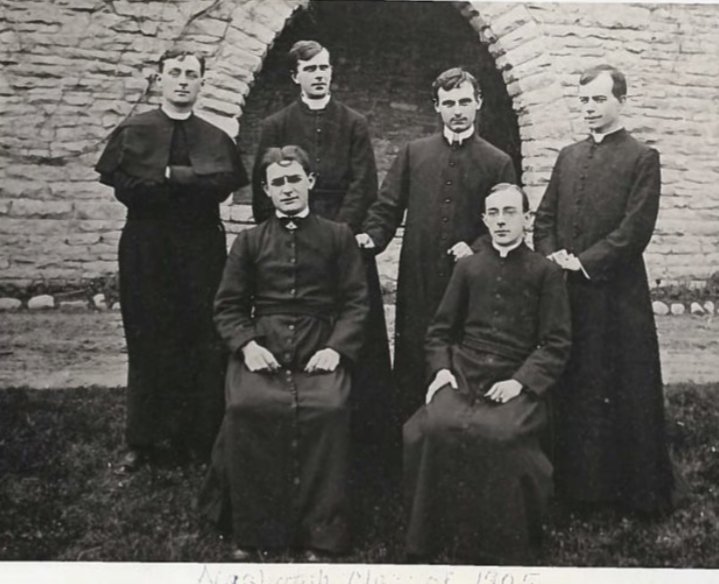

Fr. Webb studying in his office at Nashotah House.

We had very little money. There was no endowment at all and rather a large debt. The money had been loaned by various farmers in the neighborhood. They were being paid ten percent, and I remember their indignation when I took up a good many of these notes. Sometimes there was no money to pay the interest in Dr. Gardner’s day, and when he would go away for a trip, I was in charge, and I was always suspicious that the interest on some of the notes was due. We had very simple food, and the men looked after their rooms. The water was all cistern water. There were no bathrooms, except one in Lewis Hall and one in Shelton Hall. We had to pump all the water by hand into a tank on the top of Lewis Hall. The students did not like that sort of work, and Fr. Clapp and I lost a good many pounds at it, but it was probably good for us.

There was one year when we had no money to get coal, and I think there was a coal strike on, so that the coal was very expensive. That was after the cloister was built, and there was a furnace at each end of the cloister and one under Lewis Hall and one in the chapel. Dr. Gardner cut down a large amount of timber through the woods, especially on the left hand side of the road going towards Oconomowoc, and I remember how indigent the people were. But we were very hard pressed to keep the place warm, and as it was we had to shut up the chapel and have services in the oratory of Bishop White Hall, which was heated by two wood stoves.

I think most of us who were there look back to that winter as a nightmare. In those days we had to depend largely on what came in from the Daily Bread, and people who had been sending money to Nashotah for years were beginning to die, and the younger generation were not interested. I can recall a great many times when there seemed to be a very remarkable answer to our prayers, when we really did not know where the money was to come from for the food, or the very small salaries, for in those days the men who were teaching at Nashotah were receiving a really very nominal salary. Nashotah for many years had been considered one of the picturesque missions of the church and a good deal of money was sent there by what we called the Nashotah League in the East, groups of people who subscribed regularly for the work at Nashotah. The last League, I think, was in Philadelphia, of which Dr. Nicholson was the president. He was then rector of St. Mark’s Church.

For years we received an envelope with some money in it and a card simply marked “In quietness and in confidence shall be your strength” -- Isaiah 30:15. It was always entered in the books under that heading, appearing for years. Toward the end of my administration, I received a letter from a man who said that his mother had died and they had found on top of her bureau an envelope containing the money directed to Nashotah House. It was then for the first time that we knew who had sent the money for so many years.

Alice Sabine, as a little child, had heard an account of Nashotah and put her pennies in a mite box, and the money was sent each year. She never saw Nashotah, but when she died in France, she left the money in her will which built the cloister and also some money to her mother, who, after Alice’s death came to Nashotah and the money was put in the endowment fund.

There is more or less history connected with the names of the various buildings at Nashotah. The Blue House was so named because when it was built at cost, I think, the large sum of $400. Dr. Breck was presented with some bright blue paint with which he proceeded to paint the house. Shelton Hall is named after Dr. Shelton who was the Rector of St. Paul’s, Buffalo, and the money used in constructing that building largely came from his parish. Lewis Hall was named after Miss Margretta Lewis, who belonged to a well known church family in Philadelphia, and who left the money with which it was built. I have already said that the money for the cloister was left by Alice Sabine, afterwards Mrs. McGee. Bishop White Hall, which burned down and which for a long time was the only dormitory on the grounds, was so called on account of its being built when there was a strong reaction in the Protestant direction at Nashotah. The Fort was so called because Mrs. Cole supposedly influenced Dr. Cole very strongly, and the students called it Fort Betsy. Much to their amusement, it appeared as The Fort on Mrs. Cole’s notepaper stationery. The Turkey Roost, which burned down, was on the site of the small cottage where Father Whitman now lives and was the original farmhouse, added to, and used as a common room for a good many years. It later had a wing added to it by Dr. DeKoven when he had his school there. The preparatory men, as they were then called, lived there and for some reason. The men who were preparing for Dublin University, were called “sucking turkeys,” and Dr. Adams, who was a graduate of Dublin, called it the “Turkey Roost.”

There are two sites at Nashotah that I think ought to be remembered. One is just south of the cemetery in the pasture, where there is a long depression, very much like a road bed of a small narrow gauge road that goes across from the road in front of the farm house to the road to Oconomowoc. That is the remains of an old Indian trail that the Indians used to take in traveling, as I understand, from Lake Michigan west. It passed between Upper and Lower Nashotah. Dr. Adams told me that in the early days he had frequently watched long lines of Indians with their packs traveling along that trail.

Just below the extreme southwest corner of the cemetery, there are the remains of an old cellar. This was the site of the first claim house, where the first Mass and other services were said. I have always hoped that sometime or other it might be marked by a cross.

It is also interesting to know that the road in front of the farm house is said to have been surveyed by Jefferson Davis.

As I have already said, Dr. Riley was for many years the most Catholic churchman connected with the house and kept up the tradition and really carried it through the most difficult period, for which he has never received the credit that he ought to have. He had, however, one peculiarity that was not good for Nashotah. He populated the place with ghosts. Long before he came to Nashotah, there were a good many stories that he had told about things that were supernatural that he thought had happened to him. There is a picture that Father Curtiss, now rector of Sheboygan, took up in the cemetery of Dr. Gardner, then President of the House. Standing some distance away, there seems to be a figure of Dr. Cole in a cassock and biretta, and apparently he is holding something in his hands. When the doctor was buried, Mrs. Cole insisted on having a chalice and paten, which really belonged to the House, buried with him, and Dr. Riley thought that Dr. Cole had come back with the chalice and paten in his hands, to show that he disapproved of what had been done. I remember making a lantern slide out of the negative, and wanted very much to use some india ink, but I was afraid that Dr. Riley would never forgive me. I have a copy of that picture, and it is very evident that Dr. Cole’s picture is made up of a tombstone and a certain combination of leaves.

There was a story connected with Dr. Cole’s death that Dr. Riley was fond of telling. His body was lying up in the Fort and various students were keeping watch. It was a bright moonlit night, and one of the students, by the name of Sellers, returned to Bishop White Hall about midnight. He was evidently in a very nervous condition and was met by what he described as a tiny figure dressed like a little man, who kept running at him and taking off his hat. He rushed into the room and was quite ill as a result of it; in fact, later on he died--probably from the effects. He dictated to Dr. Riley a long account about his experience, which Dr. Riley took very solemnly. When I came to Nashotah, I made a number of inquiries and discovered that a monkey had escaped from Delafield and had been found on the Wing farm at the end of the north road and would have gone across the grounds at the same time that Seller’s ghost appeared. Unfortunately, Dr. Riley used to tell those and many other stories to the reporters, and once or twice they appeared at great length in the Sunday papers. Naturally, this was not a good thing for Nashotah, but it was hard to convince the Doctor that things were not supernatural but more likely that the men were perhaps playing tricks on him.

I remember once we had been looking at some plans for the cloister in Dr. Gardner’s study and laid the drawings on the table to go to dinner. In those days the Senior class sat with the faculty. We were discussing some of the Doctor’s ghost stories and he said, “Suppose we should go back and find those plans up on the top of a book case. How would you account for it?” When we got back, that is just where they were, and the Doctor was certain that the ghosts had been at work again, but Dr. Gardner drew our attention to the fact that there were some footsteps by the window, left in a light fall of snow. The Doctor couldn’t believe that the students would do such an unkind thing.

There was a time when a good many of the Nashotah men went into the mission field. A number of men went to Japan and a number to Alaska. I wish there were the same missionary spirit today. It has always been to the credit of the Virginia Seminary, that they have sent so many men into the mission field. I wish that the old missionary spirit were as strong at Nashotah as it used to be. I am afraid that the comfortable buildings and easy life have their disadvantages, and that the men are not quite as willing to do the hard things that they used to do--I think of the days when they walked to Delavan, Elkhorn, Kenosha, and Beaver Dam to hold services. Dr. Jenks and Prof. Clapp both walked to Watertown Sunday after Sunday, and students walked to North Lake and Pewaukee, as well as to many of the nearer missions. We talk a good deal about the solving of the rural problem and some years ago Bishop Anderson, in an address that he made on Domestic Missions at the General Convention in Richmond, the first General Convention at which I was present as Bishop, made the statement, much to my surprise, that of all the counties west of the Allegheny Mountains, Waukesha County had the largest number of communicants per capita. Naturally, he could only have taken representative counties to make the calculation. The reason was that we were the first on the ground and that men went out from Nashotah as a center in every direction. As we know, so many of the men still go out on mission work, and it would have been absolutely impossible for bishops of Milwaukee to have kept missionary work going throughout the diocese without the help of Nashotah. There is no more difficult work in the world for a priest than in the mission of a small town, such as we have so many in the Diocese of Milwaukee. It takes far more heroism and is much more difficult than going into the foreign field with its interest and excitement and ideas, sometimes illusions, of heroism. As Dr. Barry once said in an address on missions that he delivered at Nashotah before he was President, “If you want to make saints of yourselves, go into some of the small isolated towns and stay there.”

—

The preceding is a transcription of a “My Life at Nashotah” by the Rt. Rev. William Webb, transcribed here by Terry Koehler, whose husband, the Rev. Brien Koehler, graduated in 1976. Images courtesy Frances Donaldson Library at Nashotah House. Special thanks to the Rev. Dcn. Bramwell Richards (‘18), Electronic Services Librarian for procuring these for The Chapter.