The Street Priest

In 1959, a recent graduate of Nashotah House arrived in Orlando, Florida. Fr. Nelson Pinder, a newly ordained priest at the time, would go on to serve the Orlando community for more than 60 years. During the 1960s and 1970s, Fr. Pinder worked with white officials for peaceful racial integration in the city during the Civil Rights Movement and, now Rector Emeritus at the Episcopal Church of St. John the Baptist in Orlando, is the recipient of nearly 200 awards and honors.

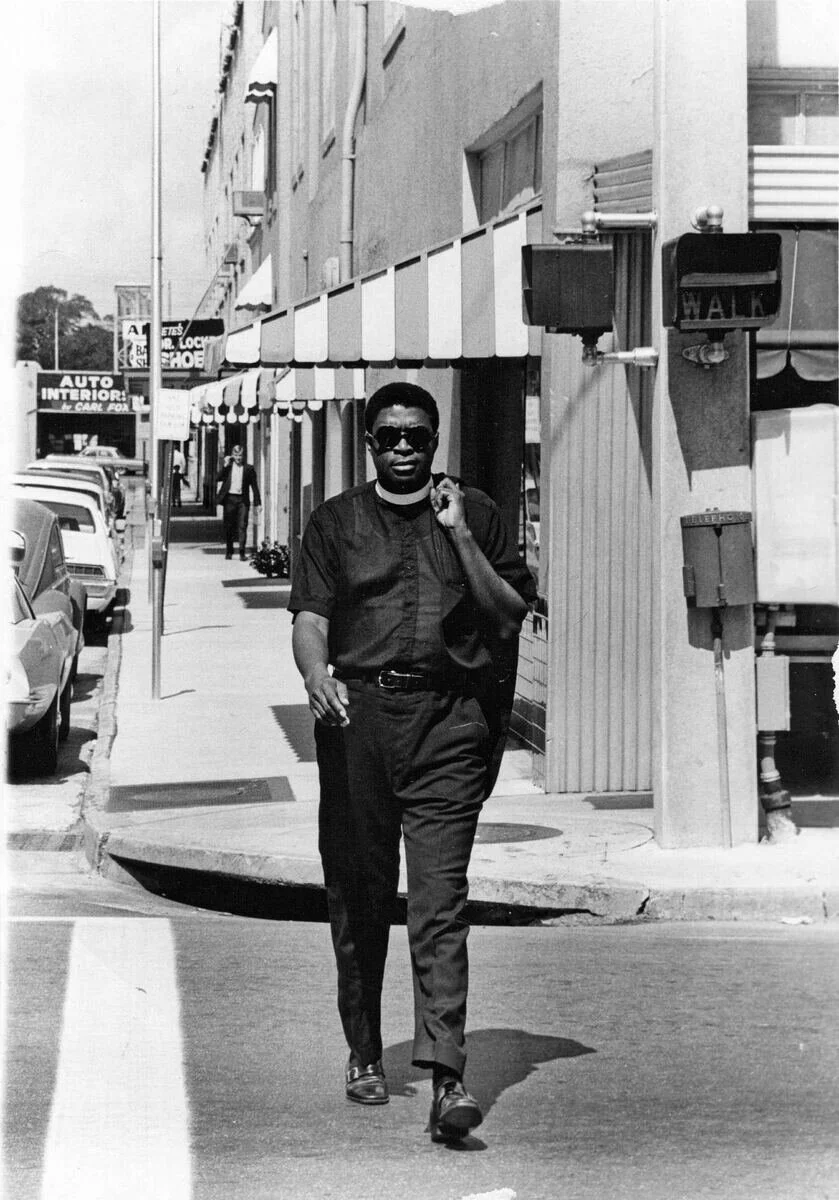

During his more than 60 years in ministry, The Rev. Canon Nelson W. Pinder has been known affectionately as the “street priest,” and the “hoodlum’s priest,” as well as a community leader in Orlando. Since being ordained at the age of 27, Fr. Pinder has followed his call ministering to the church and the greater Orlando community and is well known by historians, community organizers, and members of the Boys and Girls Club alike.

Born in Miami in 1932, Pinder enrolled in Bethune-Cookman College as a young man and was then drafted into the U.S. Army during the Korean War. After receiving an honorable discharge, he returned to college where he became active in student government and other campus groups. Pinder graduated in 1956 with a degree in philosophy and soon enrolled on The GI Bill at Nashotah House, where he trained for the priesthood. In 1959, he was ordained and assigned to The Episcopal Church of St. John the Baptist in Orlando. He married his college sweetheart, Marian Elizabeth Grant, on August 15 of that year.

“Life at Nashotah House had a strong focus on worship and community,” said Fr. Pinder. “I enjoyed visiting with all my professors, and they were always challenging me to become a good parish priest. The professor who stands out to me the most is Dean Edward S. White. We had about 25 classmates, and I remember the Dean taking me aside one day and telling me: you’ll be a damn good parish priest.”

In 1956, a typical day at “the House” involved prayer, work, and study—all with the focus of priestly formation in seminarians.

“It was a rigorous life and still is,” said Fr. Pinder. “The life of the seminary seeks to form the character of priests and Christian leaders into the image of Christ. That is not an easy thing. But one thing I knew was that Nashotah House would train me to be able to go anywhere.”

All students—then as well as now—have work crew assignments: cleaning, mowing lawns, sweeping floors, and taking on other chores and responsibilities. Nashotah House’s daily routine has many similarities to when Fr. Pinder attended, including Morning Prayer, Mass, breakfast, classes, lunch, and Solemn Evensong.

“We each had a job to do to help the seminary to maintain itself,” said Fr. Pinder. “But not only was the work to help the seminary, it was to help us as we went forth into parish life. We became the “how-to” people, developing ministries and mission, raising money, teaching, and working with the laity. The life at Nashotah House was helpful because when you got to the parish you didn’t know what you might be expected to do.”

Fr. Pinder said the reality of segregation hit him when he arrived at Nashotah House and was unable to get a haircut in a nearby town. The barber he had gone to refused to cut his hair and said, “Black people are not welcome.” Fr. Pinder and his fellow seminarian Sam Brown mentioned it to fellow student Jim Kaestner and his wife Judy. Soon afterward, several seminarians and their spouses walked downtown to see the barber and peacefully explain that he would not be cutting any of their hair.

“That’s how we were with one another,” said Fr. Pinder. “We were a community who looked out for each other; we had veterans, lawyers, a Broadway actor, and college professors, who all came together to serve the church.”

After work, prayer, and study, it was “lights out” and silence until after the chapel’s mass the next morning. Keeping a holy silence was a discipline Fr. Pinder came to enjoy. As a seminarian, he recalls many retreats, quiet days, football and basketball games with, Fr. Pinder notes, a future bishop of New York serving as their football coach and captain. In those days, Nashotah House also boasted an active theater group which met in Kemper Hall to perform T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral for the public.

Going into town would continue to be an occasional challenge for Fr. Pinder and his fellow African-American students. “One of our fellow students, who was a white attorney, would go into a restaurant ahead of us, letting the manager know he had black friends who would be joining him for dinner,” said Fr. Pinder. “If the manager was unwelcoming, our attorney friend would give a short instruction of what the law was, reminding the manager that Wisconsin was a state that did not recognize Jim Crow laws.”

Nashotah House and several other seminaries stood firm on the Christian principle that it would not affirm segregation, nor itself be a segregated institution. Many seminarians participated in writing a proclamation in 1952 against segregated seminaries, going so far as to submit the proclamation to The New York Times for publication, a very controversial decision at the time.

Upon commencement, Fr. Pinder was ordained and assigned to St. John’s by The Rt. Rev. Henry Louttit on May 30, 1959. Fr. Pinder was St. John’s second full-time priest and the first full-time African-American priest, eventually leading St. John’s to attaining parish status.

Nearly 40 years prior, Orlando had experienced the Ocoee massacre where a white mob attacked African-American residents in Ocoee, Florida, near Orlando, on the day of the U.S. Presidential election in 1920. It is estimated that nearly 70 African-Americans were killed during the riot, and most African-American-owned buildings and residences were burned to the ground. Other African-Americans living in the area were later killed or threatened with further violence.

The race riot started as a result of white attempts to suppress black voting. Mose Norman, a prosperous African-American farmer, tried to vote but was turned away twice on Election Day. Norman was among those working on the voter drive. A white mob surrounded the home of Julius "July" Perry, where Norman was thought to have taken refuge. After Perry drove away the white mob with gunshots, killing two men and wounding one who tried to break into his house, the mob called for reinforcements from Orlando and Orange County. The mob laid to waste the African-American community in northern Ocoee and eventually killed Perry. They took his body to Orlando and hanged it from a light post to intimidate other black people. Norman escaped, never to be found. Hundreds of other African-Americans fled the town, leaving behind their homes and possessions.

The Rev. Nelson Pinder in Orlando, Florida, 1960s. Image courtesy Orlando Sentinel.

When Fr. Pinder arrived in Orlando in 1959, the memory of this riot continued to resonate with all citizens. Fr. Pinder soon became active in the community, even continuing after his retirement in 1995. There, he worked with city officials for peaceful racial integration in Orlando in order to prevent incidents of civil disorder that were then occurring in other cities during the Civil Rights Movement. Fr. Pinder organized sit-in protests of segregated lunch counters and theaters in Orlando, including the Beacham Theatre. He also served as a member of the Mayor of Orlando Bob Carr’s Biracial Commission which dealt with desegregation and equal employment opportunities for African-American citizens.

Originally, before going to Florida, Fr. Pinder had hoped to work on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Interested in starting street ministries, he firmly believed God was leading him to New York.

“However, as is often the case, God and the Bishop had other things in mind,” he said. “And I was called back to Florida.”

Arriving in Orlando in 1959, Fr. Pinder landed at one of two churches that were available to him. At that time, Orlando was still reeling from the violence of lynchings and other injustices of ten years earlier in neighboring Lake County, with the Groveland Four lynchings. In 1951, with Jim Crow laws still in effect, when the U.S. Supreme Court ordered a retrial after hearing appeals by Thurgood Marshall, the Klan marched on the streets in downtown Orlando.

“The bishop called me, and I went,” said Fr. Pinder. “I had one idea of ministry, and God had another.”

Upon his arrival to Orlando, Fr. Pinder was unable to order a cup of coffee at the airport, and he was turned away from taking a taxi with white seminarians into the city.

“My agenda became simply this: Jesus,” said Fr. Pinder. “The community had another agenda: status quo.”

St. John’s is a historically black church, established in 1896, twenty years after the incorporation of the city. Meeting in a four-room frame house from which the partitions were removed, the church was led by the Rev. H. W. Greetham, an Episcopal deacon who supported himself by working for the “Old Waterworks.” Fr. Greetham instructed those who had expressed an interest in the church on evenings in their homes. On Sundays he conducted services and taught church school.

Fr. Greetham’s mode of transportation was the bicycle in a day when paved streets and street lights were unknown. One night, he was pulled from his bicycle and beaten, by “city fathers” who objected to his visits on “the wrong side of the tracks.” Continually recognized for his saintly demeanor, Fr. Greetham was a devoted deacon to the people until his death years later.

Following in these and others' footsteps, Fr. Pinder said, “I kept preaching and teaching the Gospel, and the city began to change by the grace of God and the people joining in.”

Peaceful change began with blacks and whites talking and listening to one another, allowing God to change hearts.

“I talked about the love of God and what he has given us in Jesus Christ, helping us to work together to solve our problems,” said Fr. Pinder. “When people are blind, they do not want to give up, and it took a long time for change to occur. In the meantime, I kept saying the same message: Christians do not live alone and cannot change for the better alone and asking people, ‘How can I say I love God and hate my brother and sister?’”

In response to being asked how Nashotah House helped form his ministry, Fr. Pinder said, “People will sometimes say, oh my seminary didn’t teach me what I needed to know, or I wish my seminary had taught me this and not that. I didn’t expect to be in the ministry God called me to, but along with good theology goes mission. Originally, I wanted to go to the Lower East Side and do street ministry, and I had it all planned out. Mission grows out of good theology—that’s something Dean White spoke to me about. We are to carry out the mission of God’s church—Hall’s lectures at Nashotah taught me that. God does not build on any natural capacity of ours. God does not ask us to do the things that are naturally easy for us. He only asks us to do the things that we are perfectly fit to do through His grace, and Nashotah House helped to teach this to me. What ultimately did Nashotah House give me? Humility, love, and the ability to give back.”